Your Complete Guide to Running a Good 10km | Free programs

10 kilometers. It's the natural next step for recreational runners – long enough to challenge you, short enough to fit into everyday life.

Many start with 5km and think "what's next?" Others have been running without structure for years without seeing progress. And some just want to break the magical 40-minute barrier that places you among the absolute best recreational runners.

But regardless of where you start: 10km requires more than just running twice as far as 5km. It requires strategy, mental endurance, and the right progression.

At Nordic Performance Training in Copenhagen, we've coached hundreds of runners from their first 5km to their best 10km time – from beginners struggling through the distance to experienced runners breaking the 40-minute barrier. And if there's one thing we've learned, it's this: Successful 10km training isn't about running as much as possible, but about training strategically, progressively – and smart.

This guide is for you who want to run 10km – whether it's your first or your fastest. We give you three complete 12-week programs tailored to your level, based on physiological principles and practical experience from runners across Copenhagen.

Why Run 10km?

10km is the perfect distance for serious recreational runners. It's long enough to require dedication and structure, but short enough to fit into a busy life without taking over.

For a person weighing 75 kg, a 10km run means a calorie burn of approximately 750-900 calories – more than a full meal. But the calories aren't the biggest gain.

10km gives you:

- The opportunity to develop deep aerobic capacity

- Experience managing pace over longer distances

- Training in mental endurance when your body starts to protest

- Insight into the balance between speed and endurance

- A proven distance in the running community worldwide

Research shows that regular running training not only improves fitness and muscle strength, but also sleep quality, mental wellbeing, and stress resistance. For many of our clients, 10km isn't just exercise – it becomes their way of mastering challenges.

Success Stories from Nordic Performance Training in Copenhagen:

Martin, 39, project manager from Østerbro

Before: Had completed Nordic Performance Training's 5km program and could run 5km in 28 minutes, but felt dissatisfied and wanted more. Had no structure in his training and just ran "a bit longer" each week.

After 12 weeks with Program 1 (5km to 10km): Completed his first 10km at Harbor Run in 58:32, has built a solid aerobic base and can now run 10km consistently 2-3 times per month.

"The jump from 5km to 10km felt enormous at first. But the program taught me that it's about patience. The long, easy runs were a revelation – I thought I had to run fast all the time. Now I understand why elite runners often spend 80% of their time on low-intensity training."

Camilla, 33, doctor at Rigshospitalet

Before: Could run 10km, but without structure. Same pace every time (around 6:30/km), felt stuck and could never improve her time. Ran typically 3-4 times per week but without variation.

After 12 weeks with Program 2 (65 to 50 min): Ran 10km in 54:18 at the Women's Run, has learned to vary intensity and now understands the importance of recovery and threshold training.

"I thought more training = better results. But I just ran 'moderately hard' all the time and was constantly tired. The program taught me to run 80% of my runs MUCH slower – and the 20% intervals really hard. The paradox is that I train less now, but have become much faster."

Lars, 42, architect from Frederiksberg

Before: Experienced recreational runner with 10km time around 45-46 minutes. Wanted to break the 40-minute barrier but had hit a plateau. Lacked specific VO2max training and race strategy.

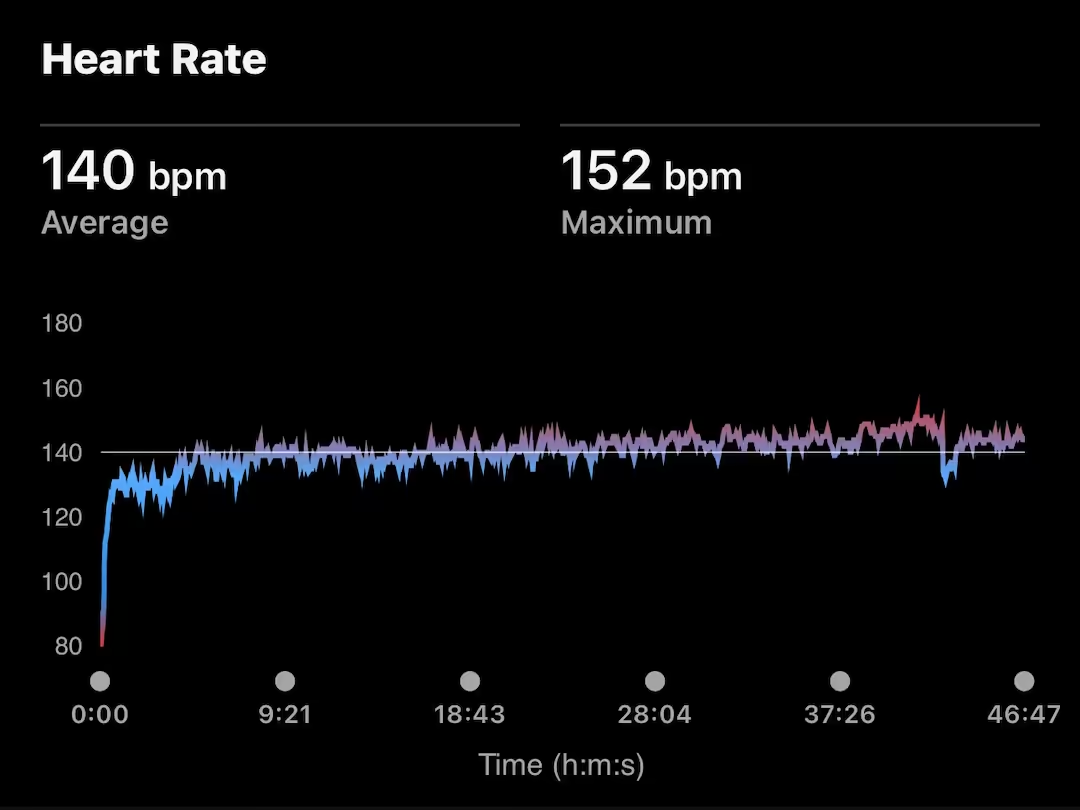

After 12 weeks with Program 3 (45 to 39 min): Ran 10km in 39:42 at Royal Run in Copenhagen 10km split, average heart rate 178 bpm (92% of max). Has increased his VO2max from 48 to 54 ml/kg/min.

"Breaking 40 minutes on 10km was a huge goal for me. The program was really intense – 5×1200m intervals with only 90 seconds rest felt impossible at first. But the body adapts. The mental part was hardest: holding just under 4:00/km pace when it hurts. Now the goal is to maintain my fitness level as long as I can."

What is a Good 10km Time?

10km times vary enormously depending on age, gender, training background, and natural abilities. The most important thing is to focus on your own progression rather than comparing with others.

Benchmarks for different levels:

- Beginners (65-75 minutes): Solid first attempt if you have a 5km base

- Lightly trained (55-65 minutes): Good performance for regular recreational runners

- Trained (45-55 minutes): Requires structured training and consistency. A time under 50 minutes places women in the top 20-25% and men in the top 30-35%

- Well-trained (40-45 minutes): Requires years with a solid base and periodized training. Under 45 minutes places women in the top 10% and men in the top 15%

- Elite (under 40 minutes): Requires high VO2max, excellent running economy, and dedicated training. Under 40 minutes places men in the top 5-7% and women in the top 2-3%

Remember: A "good" time is a time that represents progress for you. Successful 10km running is about continuous improvement, not reaching specific benchmarks.

10km-Specific Knowledge: From 5km to 10km

What's the Physiological Difference?

10km isn't just "double 5km". Here are the important differences:

Energy Systems:

- 5km: Primarily anaerobic threshold (85-95% of max HR) – you're flirting with "the red zone"

- 10km: Aerobic-anaerobic balance (80-90% of max HR) – you need to maintain high pace sustainably

Mental Game:

- 5km: Intense from start to finish – over in 20-30 minutes

- 10km: "The difficult middle" (km 4-7) where doubt comes – requires mental discipline

Pacing:

- 5km: Can be started aggressively – less penalty for mistakes

10km: Mispacing the first 3km can ruin the entire race

Pacing Strategies for 10km

Negative Split Approach (recommended for most)

Start 5-10 seconds/km slower than your goal pace for the first 3-4km, hold steady km 4-7, and accelerate km 8-10.

Example - goal 50 min (5:00/km pace):

- Km 1-3: 5:05-5:10/km (warm up, find rhythm)

- Km 4-7: 5:00/km (steady state, mental focus)

- Km 8-9: 4:55/km (starting to push)

- Km 10: 4:45/km (everything you have)

Benefits:

- Conserves energy early

- Builds mental momentum

- Better physiologically – less lactate early

- You pass people at the end (mental boost)

Even Split Approach (for experienced runners)

Hold exactly the same pace throughout.

Example - goal 40 min (4:00/km pace):

- Km 1-10: 4:00/km (±2 seconds)

Benefits:

- Optimal energy utilization

- Requires less mental energy

- Assumes perfect knowledge of own capacity

Race Nutrition for 10km (40-65 min runs)

Before the Race:

3-4 hours before:

- Light meal with carbohydrates: oatmeal with banana, bread with honey, muesli

- 400-600 ml water

60-90 minutes before:

- 1 banana or energy bar (25-30g carbohydrate)

- 200-300 ml water

15-30 minutes before:

- 1-2 energy chews or small gel (if you're used to it)

- 100-200 ml water

During the Race:

For runs under 50 minutes:

- Typically NOT necessary with nutrition

- Water/sports drink at km 5 if it's hot (>20°C)

For runs 50-65 minutes:

- Consider 1 gel at km 6-7 if you feel energy dropping

- Water/sports drink at km 5-6

Important note: Test EVERYTHING in training first. Race day is not the time to experiment.

Mental Strategy: "The Difficult Middle" (km 4-7)

10km is long enough for doubt to creep in. Here's how you handle it:

Km 1-3: "The Comfortable Start"

- Mental state: Optimism, energy, excitement

- Strategy: Hold back. It feels easy – it's a trap.

- Mantra: "Trust the plan, not the feelings"

Km 4-7: "The Difficult Middle"

- Mental state: Doubt begins. "Can I hold this pace for 6km more?"

- Strategy: Mental chunking – only think to the next kilometer

- Mantra: "One kilometer at a time. I've handled worse in training."

Concrete techniques:

- Count breathing (1-2-3-4) to focus

- Find a runner ahead of you – "I'm just hanging on"

- Remember your best training sessions: "I ran 5×1200m harder than this"

Km 8-10: "The Final Push"

- Mental state: Pain, but also hope – "I'm almost there"

- Strategy: Aggressive thoughts. "Attack the finish"

- Mantra: "Accept the pain. This is where personal records are set."

Concrete techniques:

- Visualize the finish line

- "Count down" - only 2km, only 1km, only 500m

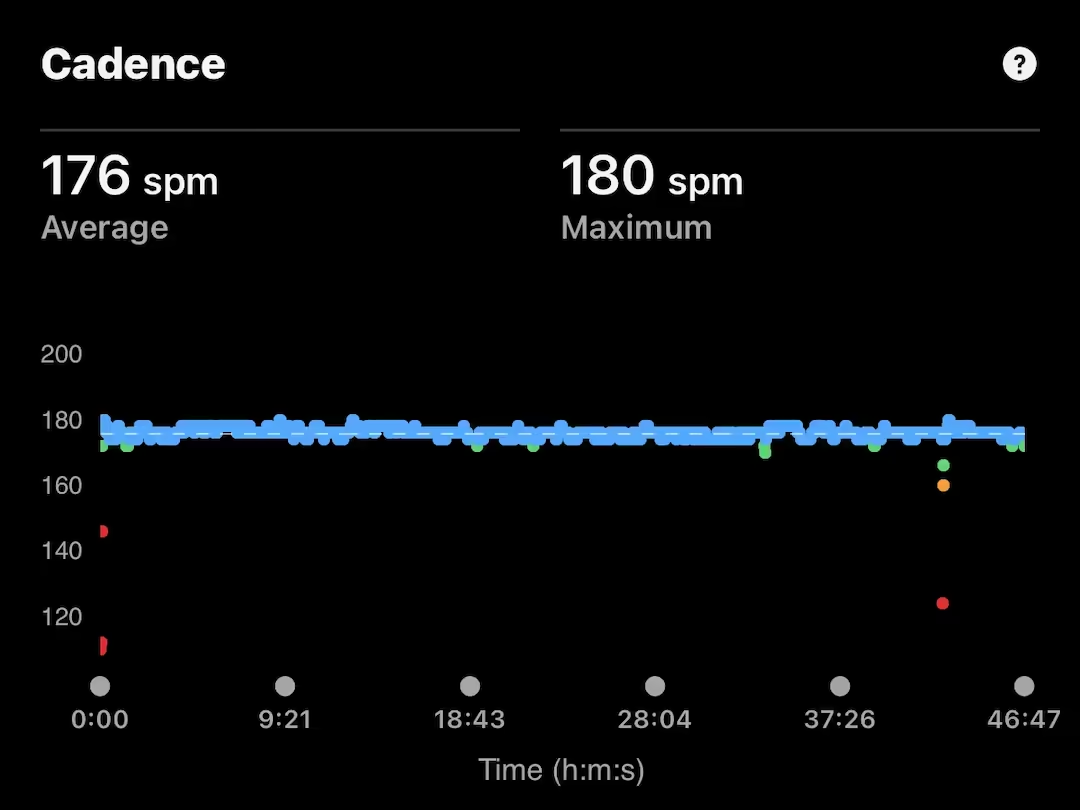

- Increase cadence by 5 steps/min (gives feeling of acceleration without massive effort)

Different Training Types in a Running Program

If you want to improve at running 10km, it's important to combine different types of training. But first and foremost, it's about building good basic fitness and aerobic capacity.

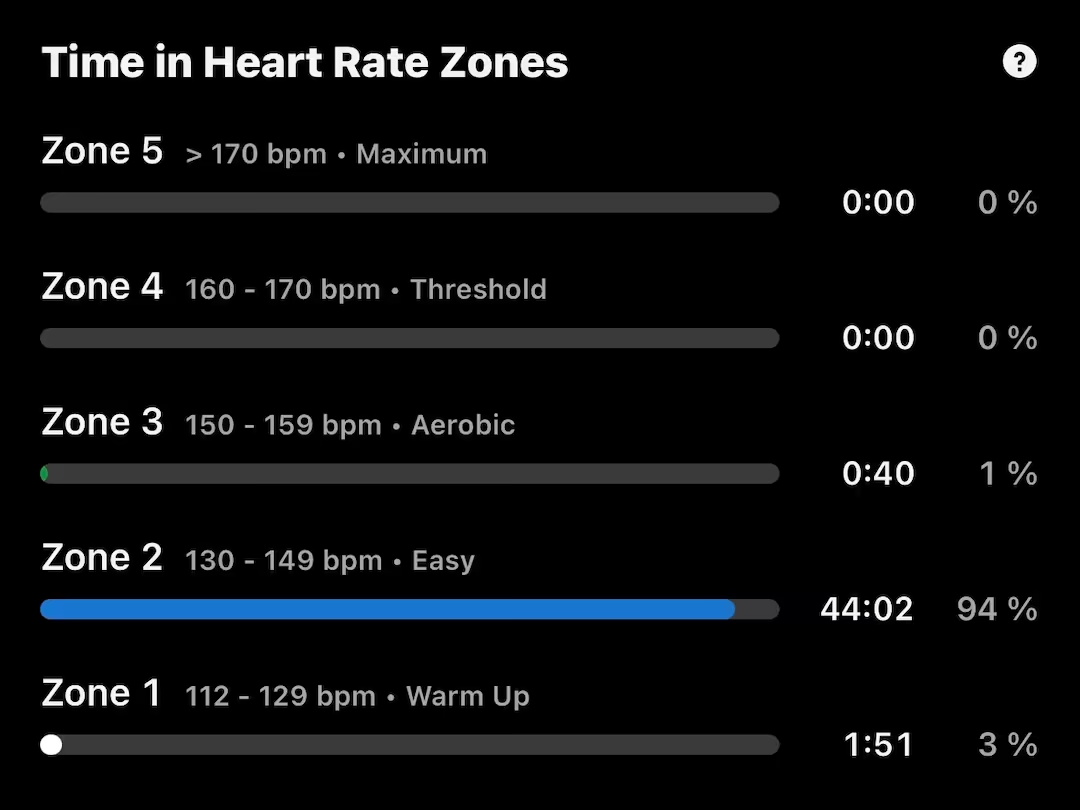

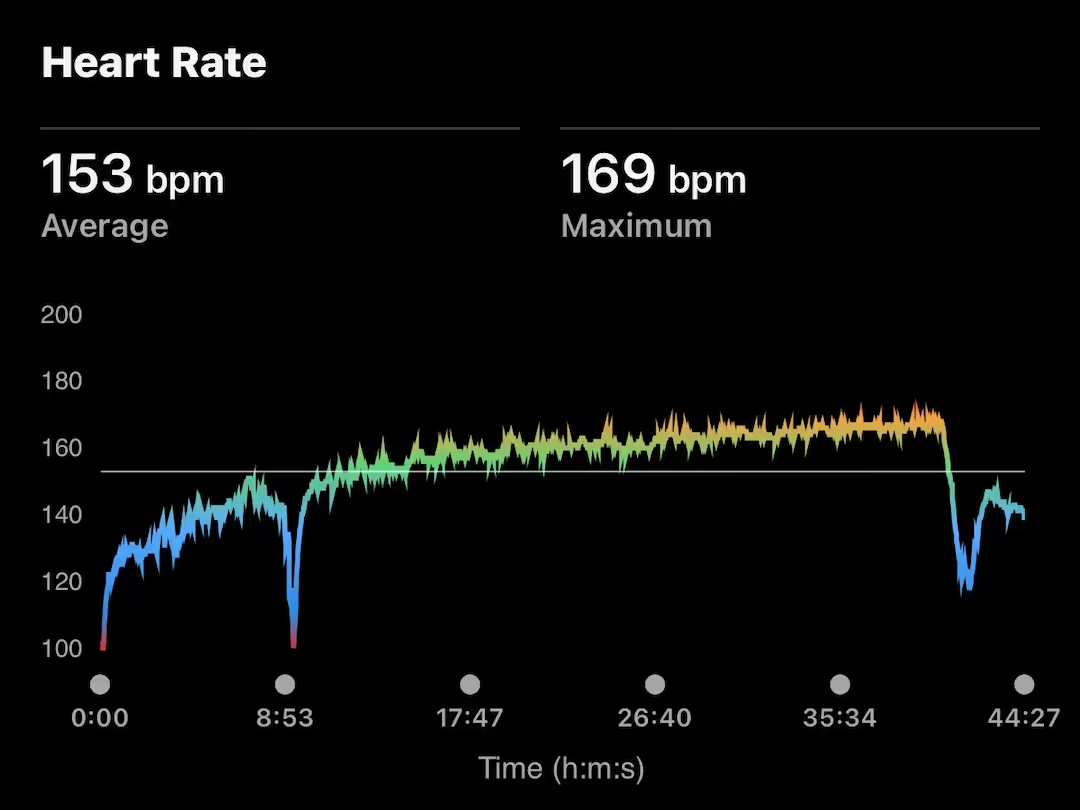

Easy Runs (Z2)

The easy and longer runs are the foundation of all running training. Here you run at a pace where you can talk without getting out of breath (70–80% of your max heart rate). It helps the body get better at using fat as energy and builds your fitness.

Note: Zone 1 training (50-70% max HR) exists, but is primarily used by long endurance athletes who train 10+ hours per week. For 10km runners with limited time, Z2 gives superior aerobic development per training minute.

Why it works: Your body gets better at burning energy, your heart gets stronger, and more small blood vessels (capillaries) form in the muscles. This enables you to run longer and faster.

The 80/20 distribution, where approximately 80% of training takes place at low intensities and 20% at high intensities, is supported by recent meta-analyses. This polarized approach proves particularly effective for improving VO2max, especially in well-trained athletes and in shorter training periods (under 12 weeks).

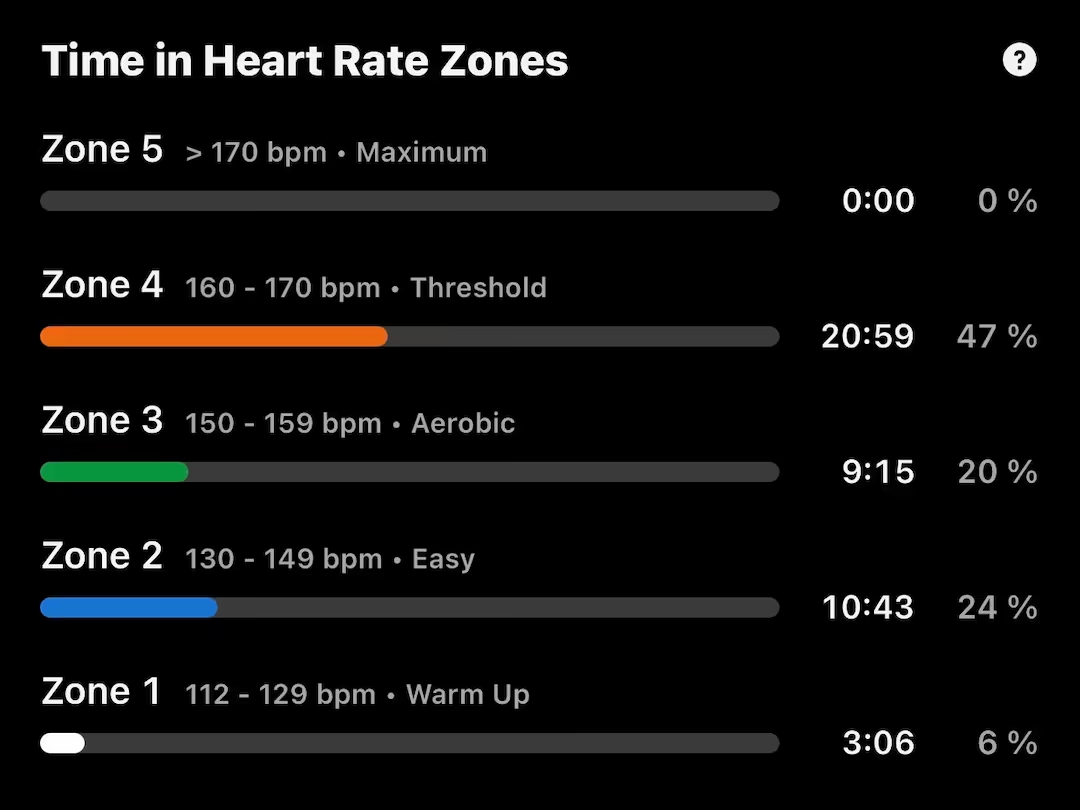

Tempo Runs and Threshold Training (Z3/Z4)

These are runs at a pace that feels hard, but which you can maintain for 20–75 minutes. This corresponds to approximately 80–90% of max heart rate.

Note: Technically, tempo runs are Z3 (aerobic threshold), while threshold runs are Z4 (anaerobic threshold), but for practical training purposes, this Z3-Z4 range develops similar adaptations.

Purpose: To train the body to get better at handling the fatigue that comes when you run fast.

Interval Training (Z4/Z5)

Here you alternate between shorter periods of hard running and breaks where you walk or run slowly. For 10km runners, intervals are typically 800-2000 meters.

Note: Intervals typically mix Z4 and Z5 intensities depending on length and your fitness level.

Purpose: To improve your fitness and ability to maintain high pace over longer time.

Strides

Short, controlled accelerations of 80-100 meters performed at the end of easy runs. Complete 3-6 strides with 30-60 seconds of fast running (approximately 90% of your sprint speed) followed by full recovery between each repetition.

How to perform strides:

- Jog at an easy pace (Z2)

- Gradually accelerate over 20 meters to approximately 90% of your top sprint

- Hold the speed for 30-60 seconds

- Gradually decelerate over 20 meters

- Continue jogging or walk slowly until fully recovered (heart rate should come down)

- Repeat 2-5 more times

When: After easy runs, when muscles are warm but before you're fatigued. Never on rest days.

Why strides are invaluable: Strides improve running economy, neuromuscular coordination, and make your race pace feel natural without creating fatigue. They are one of the most time-efficient ways to improve your 10km performance.

Personal recommendation: I like to do 3-4 strides at the end of my easy runs, but I never allow my heart rate to stay elevated, as it's still meant to be an easy run.

Before You Start – Important Preparation

Equipment – What You Actually Need

You don't need expensive equipment to run 10km. But the right equipment makes training more comfortable, more precise, and reduces the risk of injury.

Running Shoes - Your Most Important Equipment

The most important equipment is your shoes. You don't need to get a running gait analysis from a shop assistant – unless you're an elite athlete, it's more important that you start with comfort and cushioning rather than biomechanical perfection.

Here are our recommendations based on level:

Beginners: Start with a max cushioned running shoe – soft, shock-absorbing and forgiving, so you can get started without too much soreness.

Lightly trained: Combine a max cushioned shoe for easy runs and a daily trainer or lightweight "race" shoe for faster paces. If the budget only stretches to one shoe, choose a versatile daily trainer.

Experienced runners: We recommend the following rotation:

- Max cushioned (recovery)

- Daily trainer (everyday use and speed sessions)

- Race shoe (test days, PR attempts and competition)

- Bonus: Multiple versions of all the above, if you're a shoe connoisseur

Our favorites running shoes:

Clothing

The best materials for running are polyester, nylon, spandex, bamboo, and merino wool, because they are breathable, sweat-wicking, and flexible. If you want to avoid plastic and fossil-based materials, merino wool and bamboo are an obvious choice – they also have natural antibacterial properties, which reduce odor.

Avoid cotton, as it absorbs moisture, becomes heavy, and increases the risk of discomfort and chafing during running.

Think in Seasons – and Layer Upon Layer

If you want to plan your running clothes a bit more long-term, it makes sense to think in three seasons:

Summer: Here it's about as little and as airy as possible. Choose light materials and short tights or shorts, t-shirt or tank top. Keep focus on breathability.

Spring / Autumn: Use the same basic structure as in summer, but switch, for example, tank top for long-sleeved running shirt, and short tights for long tights or running pants. Layer-upon-layer makes it easy to regulate temperature according to conditions.

Winter: Winter requires a bit more consideration – but you don't need to freeze:

- Start with a long-sleeved base layer (if you get very cold, choose, for example, merino wool)

- Add a slightly thicker shirt or light running jacket on top

- Choose either thermo tights or the combination of tights + loose pants on top

- Merino wool is particularly suitable in winter, because it both warms, breathes, and resists odor.

Small things that make a big difference in winter:

- Waterproof gloves: Choose a slightly larger size than normal, so you can have a thin merino wool glove underneath

- Neck gaiter/snood: Keeps you warm without feeling suffocated and can easily be pulled up when you're cold, or down if you get warm

- Light rain jacket: Ideal in unstable weather – takes up almost nothing and can be taken off along the way

In Copenhagen, the weather changes quickly – if in doubt, take an extra layer with you. It's much easier to take off than to freeze through the run.

GPS Watch and Heart Rate Monitoring

You can go far with free apps like Strava on your phone. But a good GPS watch helps you with:

- Seeing pace and distance in real time

- Measuring your heart rate zones and progression

- Keeping structure in intervals and training plan

A good running watch can quickly become your best friend on runs, keeping you on track and telling you both if you're slacking, but also if you're pushing yourself too hard.

Top 3 GPS Watches:

Apple Watch? Works fine, but is limited in terms of intervals and heart rate data. It's still primarily a smartwatch – not a dedicated running watch.

Personal recommendation: Make sure the watch has music storage - it's just a bit cooler to run with music without having to carry your phone.

Heart Rate Monitor (Extra Precision – Not Necessary)

A heart rate monitor (typically chest strap or armband) can provide much higher accuracy than optical heart rate measurement from your wrist – especially during intervals and tempo runs. It's not a requirement, but a good investment if you want to nerd out more with zones.

Top 3 Heart Rate Monitors:

Conclusion: Start simple. One pair of shoes and a phone app is enough to get started. But if you want to track your progress, understand your zones, and train targeted, a GPS watch and some good running shoes can quickly become your best training partners.

Warm-up, Cool-down and Injury Minimization

Warm-up is important, but it's not a magic solution. Many runners think that a little stretching or some hip swings can prevent injuries – but unfortunately that's not enough. It's especially important to warm up well before harder training like intervals, tempo runs, or threshold sessions. For calm, easy runs (easy runs), thorough warm-up is usually not necessary.

A good warm-up helps reduce the risk of injury on the day, improves your experience during the run, and helps the body find rhythm. But the most important thing to avoid injuries is to take care of your training volume. If you increase distance or intensity too quickly, you significantly increase the risk.

Research shows that around 40% of runners experience injuries each year – and in most cases, it’s due to excessive load, not a lack of warm-up, cool-down, or stretching exercises.

Warm-up (5–10 minutes)

For most people, it's about starting calmly and gradually increasing pace.

Standard warm-up before most running sessions:

- 3–5 minutes slow jog or brisk walk (Z1–Z2)

- 3–5 minutes with varied pace (e.g., short 15-30 second accelerations)

Optional dynamic exercises (especially before intervals or tempo sessions):

- 10 × leg swings forward/backward per leg

- 10 × hip circles per direction

- 10–15 × knee lifts in place

- 20–30 bodyweight squats or 10–15 split squats per leg

These exercises warm up hips, ankles, and legs and improve mobility without draining energy.

Cool-down (5–10 minutes)

Cool-down is not magic and not necessary, but can help finish training calmly.

Standard cool-down:

- 5–10 minutes slow jog, walk/run combination or brisk walk

Optional static stretching (only if it feels good, no documented effect on recovery):

- Calf: 30–60 seconds per leg

- Front thigh: 30–60 seconds per leg

- Back thigh: 30–60 seconds per leg

Important Points

- The harder the training, the more important the warm-up.

- For most recreational runners, it's more important to start calmly, increase gradually, and let the body get used to the load than to do a "perfect" warm-up.

- At Nordic Performance Training, we most often see injuries arise when people start too hard – with too long, too fast, or too frequent training. Slow, structured progression is more important than anything else.

Listen to Your Body – Distinguish Between Soreness and Injury

Normal soreness:

- Diffuse muscle fatigue 24–48 hours after training

- Improves with light movement and heat

- Doesn't affect running style or function

Warning signs of injury:

- Sharp, localized pain during running

- Pain that worsens with activity

- Swelling or visible inflammation

- Pain lasting more than a week

If you experience warning signs, you should take a break and possibly seek help from a physiotherapist or running coach.

Basic Running Technique

The most important first: It's not your running style that determines whether you get an injury. It's how you dose your training.

The most well-documented factor in preventing running-related injuries is what we call load management – that is, how quickly and how much you gradually increase your training volume. This applies regardless of whether you land on your heel, midfoot, or forefoot.

Basic principles in good load management:

- Increase slowly and steadily in volume or intensity

- Listen to your body – beginning pain should be respected, not overruled

- Use appropriate running shoes for your needs

- Ensure enough recovery – sleep, food, and breaks also count

That said, running style can play a role – but not in the way many think. There is no one "perfect" running style, and many of the fastest and most durable runners have running styles that would get criticism from many experts. This doesn't mean that running style is irrelevant – it just means that it should be seen in context with the individual runner's needs, injury history, and preferences.

Good, general advice about running style:

Cadence (step frequency): Research shows that a higher cadence (around 170–190 steps per minute) can improve biomechanics and reduce certain load parameters per step. However, the evidence for direct injury prevention is limited. Shorter, more frequent steps may offer potential benefits – but should always be adjusted to the individual runner’s height, leg length, and natural movement pattern.

Landing pattern: It's not about heel vs. forefoot. There is no clear evidence that one type of landing is better than others. The most important thing is that you don't over-stride – that is, land with your foot far in front of your body. This creates braking force and increases load. The goal is to land with your foot approximately under your center of gravity – regardless of where on your foot you land.

Body posture: Avoid "sitting back" with bent hips and forward-bent head. Think "long back" and a light, collected forward-leaning body posture – like a 100m sprinter.

Relaxation: Tense shoulders, arms, and hands cost unnecessary energy and discomfort. Aim for a relaxed, elastic run. Lightness and rhythm are more important than precision.

What you should be critical of:

There are many myths about running style – and not all are grounded in reality:

- "You should run on your forefoot" – not necessarily, and for many it can increase injury risk

- "Minimalist shoes prevent injuries" – this is not documented, and many experience the opposite

- "Pronation is dangerous" – pronation is a natural and necessary part of the foot's shock absorption

- "One should correct running style to avoid injuries" – only in cases of persistent problems and always individually.

Conclusion: Focus on What Works

Progressive loading over time is more important than your running style. But if you experience recurring problems, small adjustments in technique can be helpful – preferably with professional sparring.

And remember: an "ugly" running style is not necessarily bad running style. It's efficiency and injury history that count – not aesthetics.

Choose Your Free 10km Running Program

Here you get 3 structured programs for different starting points. All programs follow the same physiological principles: gradual progression, periodized intensity, and sufficient recovery.

Each program contains 3-4 weekly running sessions plus 1 optional day for extra base/foundation.

The last 2 weeks before your 10km test are critical for optimal performance. Week 11 is your "dress rehearsal," where you practice race pace under controlled fatigue. Week 12 is tapering - reduced volume but maintenance of intensity, so the body recovers while you maintain sharpness.

Running Program 1: From 5km to 10km (12 weeks)

For you who can run 5km and want to bridge to 10km

This program gradually builds your aerobic capacity and gets you used to longer distances. You start with mixed 5km + extra and progressively extend until you can complete 10km.

Week 1-4: Base building

- Session 1: 6km easy run (Z2) + 4 strides

- Session 2: 3×800m (Z4), 90 sec rest

- Session 3: 5km easy run (Z2)

- Session 4 (optional): 4-5km easy run or walk

Week 5-8: Volume progression

- Session 1: 8km easy run (Z2) + 4 strides

- Session 2: 4×1000m (Z4), 2 min rest

- Session 3: 15 min threshold (Z3-Z4)

- Session 4 (optional): 5-6km easy run

Week 9-10: Specialization

- Session 1: 10km easy run (Z2) + 5 strides

- Session 2: 5×1000m (Z4-Z5), 90 sec rest

- Session 3: 20 min threshold (Z3-Z4)

- Session 4 (optional): 6-7km easy run

Week 11: Test week

- Monday: 8km easy (Z2) + 4 strides

- Wednesday: 3×2000m at 10km pace, 2 min rest

- Friday: 5km recovery jog

- Sunday: 8km test run – goal: feel your 10km race pace

Week 12: Taper and race week

- Monday: 5km easy + 4 strides

- Wednesday: 4×800m at 10km pace, 90 sec rest

- Friday: 3km shakeout or rest

- Sunday: 10km race!

Pacing tip: Start 10-15 sec/km slower than you think. The last 3km should feel harder than the first 3km.

Running Program 2: From 65 to 50 minutes (12 weeks)

For you who can run 10km but lack structure and variation

This program introduces polarized training (80/20), threshold work, and VO2max development. You learn to vary intensity strategically.

Week 1-4: Aerobic base + introduction to structure

- Session 1: 10km easy run (Z2) + 5 strides

- Session 2: 4×1200m (Z4), 2 min rest

- Session 3: 20 min threshold (Z3-Z4)

- Session 4 (optional): 6-8km easy run

Week 5-8: VO2max focus + volume

- Session 1: 12km easy run (Z2) + 6 strides

- Session 2: 5×1200m (Z4-Z5), 90 sec rest

- Session 3: 25 min threshold (Z3-Z4)

- Session 4 (optional): 8-10km easy run

Week 9-10: Race-specific training

- Session 1: 14km easy run (Z2) + 6 strides

- Session 2: 6×1000m (Z5), 90 sec rest

- Session 3: 30 min threshold (Z3-Z4) or 6km at 10km pace

- Session 4 (optional): 8km easy run

Week 11: Test week

- Monday: 10km easy (Z2) + 5 strides

- Wednesday: 4×1500m at 10km pace (~5:00/km), 2 min rest

- Friday: 6km recovery jog

- Sunday: 8km test run at race pace (goal: 5:00/km)

Week 12: Taper and race week

- Monday: 6km easy + 5 strides at 10km pace

- Wednesday: 5×800m at race pace, 90 sec rest

- Friday: 4km shakeout or rest

- Sunday: 10km race – goal: under 50 minutes

Pacing tip: Start first 2km at 5:05-5:10/km. Km 3-7 at 5:00/km. Km 8-10 under 5:00/km.

Running Program 3: From 50 to 40 minutes (12 weeks)

For experienced runners with solid base and high ambitions

This program requires dedication. Focus on VO2max, race-specific pace, and mental toughness. Sub-40 is elite territory.

Week 1-4: Strengthen aerobic base

- Session 1: 12km easy run (Z2) + 6-8 strides

- Session 2: 5×1200m (Z4-Z5), 2 min rest

- Session 3: 30 min threshold (Z3-Z4)

- Session 4 (optional): 8-10km easy run

Week 5-8: VO2max + race pace

- Session 1: 15km easy run (Z2) + 8 strides

- Session 2: 6×1200m (Z5), 90 sec rest

- Session 3: 6km at 10km race pace (~4:10/km) + 4×300m (Z5)

- Session 4 (optional): 10-12km easy run

Week 9-10: Sharpness + specificity

- Session 1: 16km easy run (Z2) + 8 strides

- Session 2: 5×1600m (Z4-Z5), 2 min rest

- Session 3: 8km at 10km pace (~4:05/km)

- Session 4 (optional): Light activity

Week 11: Test week

- Monday: 12km easy (Z2) + 6 strides at race pace

- Wednesday: 4×2000m at 10km pace (~4:00/km), 2 min rest

- Friday: 6km recovery jog

- Sunday: 8km all-out test – see how close to 4:00/km you can hold

Week 12: Taper and race week

- Monday: 8km easy + 6 strides at 10km pace

- Wednesday: 6×800m at race pace (3:55-4:00/km), 90 sec rest

- Friday: 4km shakeout + 4 strides

- Sunday: 10km race – goal: sub-40

Pacing tip: Start at your goal pace (4:00/km) from km 1. This is mental warfare – embrace the discomfort. Trust your training.

Guide to Intensity Zones / Heart Rate Zones

For many new runners, training terminology can seem confusing. Here's a simple, practical guide to how you should train at different intensities.

Zone 2 - Easy Pace (Conversational Pace)

This is your base pace. You should be able to speak in full sentences while running. If your running partner asks "Where should we run next time?" you should be able to answer a full sentence without being interrupted by breathing.

- Approximately 70-80% of your maximum heart rate

- Feels "comfortably hard" – you can physiologically continue for several hours, if your legs allow it

- This builds your aerobic base and constitutes the majority of your total running training

Zone 3-4 - Tempo/Threshold

You can say individual words or short sentences, but not hold a longer conversation. You're conscious of your breathing, but not out of breath.

- 80-90% of your maximum heart rate

- The pace you can hold for 20-75 minutes depending on level

- Improves your "anaerobic threshold" – the point where lactate starts to accumulate

Zone 4-5 - Intervals

Zone 4 – "Very hard"

- You can only say individual words

- 80–90% of max HR — close to your 10km pace

- Feels hard but sustainable for 15–30+ minutes

Zone 5 – "Everything you have"

- Speaking is impossible

- 90–100+% of max HR

- Typically sustainable for 1–5 minutes, depending on level

Practical Intensity Control Without a Heart Rate Monitor

Many beginners don't have a heart rate monitor. Here are alternative methods:

Talk Method:

The most reliable for beginners. Try to say "I'm running around the Lakes right now" during running:

- Z2: You can say the entire sentence naturally

- Z3-Z4: You need to take 1-2 breaths in the middle of the sentence

- Z4-Z5: You can only say "I'm running" before you need to breathe

- Z5: You cannot speak at all

RPE Scale (Rate of Perceived Exertion) 1-10:

- Z2: 5-6/10 (light-to-moderate effort)

- Z3-Z4: 7-8/10 (hard effort)

- Z4-Z5: 8-9/10 (very hard effort)

- Z5: 10/10 (maximum effort)

The Science Behind the Zones

Each intensity zone stimulates different physiological adaptations:

Z2 training develops your cardiovascular system, increases the number of mitochondria in your muscles, and improves fat burning. It's the foundation for all running.

Z3-Z4 training improves your body's ability to transport and use oxygen efficiently. It raises the speed you can run without accumulating lactic acid.

Z4-Z5 training pushes your heart-lung system to maximum capacity and improves your neuromuscular power – the ability to run fast when it counts.

All three zones are necessary for optimal 10K performance. The programs balance them strategically to maximize your results.

Running Routes, Motivation & Practical Advice

Copenhagen's Best 10km Running Routes

Amager Beach Park Loop (10km)

Starting point: Øresund Metro Station / entrance to Amager Beach Park at Øresundsvej

Terrain: Flat asphalt, minimal traffic

Benefits: Perfect for tempo runs and 10km tests. Ocean view, wide path, almost no traffic lights. Can easily be extended to 12-15km.

The Lakes + Frederiksberg Gardens (10.5km)

Starting point: Dronning Louises Bro

Route: All 3 lakes + a lap in Frederiksberg Gardens

Benefits: Varied terrain, beautiful, popular among runners

Harbor Promenade (10km out-and-back)

Starting point: Nyhavn

Route: North to Svanemølle Beach and return

Benefits: Flat, scenic, minimal traffic

Fælled Park + Ryparken Loop (10km)

Starting point: Nørrebro Station

Benefits: Soft grass surface possible, open stretches perfect for intervals

Amager Fælled Loop (10km)

Starting point: Islands Brygge Metro Station

Terrain: Flat asphalt and gravel, minimal traffic

Advantages: Perfect for tempo runs and 10km tests. Nature, wide paths, no traffic lights. Can easily be extended to 12-15km out to Royal Golf.

Maintain Continuity by Making It Easy

The biggest challenge in 10km training isn't physical, but mental. Here are concrete strategies that work:

Train at the Same Time

Your best intentions mean nothing if training competes with everything else in your calendar. Many of our clients in Copenhagen find success with:

- Morning runs (6:30-7:30): Fewer people, fresh air, starts the day positively

- Lunch break (12:00-13:00): Perfect for short training sessions, but requires planning

- After work (16:00-18:00): Good way to "switch gears" between work and leisure

Find a Running Partner or Group

Accountability works. Consider:

- Run with a good friend or partner

- Colleague with the same goal and schedule

- Online communities like Strava groups for Copenhagen runners

- Local running clubs like Sparta, FIF, or Copenhagen Marathon

Nutrition, Recovery & Strength Training

Nutrition, Supplements, and Timing

You don't need to revolutionize your diet to run 10km, but some simple adjustments help:

- 2-3 hours before running: Light meal with carbohydrates (oatmeal, banana, bread, muesli bar)

- 30-60 minutes after running: Combination of protein and carbohydrates

- Fluids: Drink 200-400 ml water 15-20 minutes before running. For runs under 60 minutes, sports drinks and gels are typically not necessary.

Remember! Better to need to pee than to dehydrate.

If you want to supplement with some supplements, you can advantageously read our article [What Are Supplements? Expert Advice from 3000+ Clients] or [Top 5 Best Supplements for Health and Training [2025 Guide]].

Rest Days Are Important

Recovery isn't inactivity – it's active rebuilding. On your rest days:

- Take light walks (Amager Beach Park, Fælled Park, The Lakes)

- Focus on good sleep (7-9 hours)

- Remember to strength train!

Strength Training for Runners

One of the most overlooked factors in running training is strength training. Many runners believe that more running training automatically makes them better runners, but research shows otherwise.

Structured strength training can improve your running economy and potentially reduce injury risk – especially when training is supervised and targeted. But the effect is more nuanced than many think.

Benefits of strength training for runners:

Injury prevention: Meta-analyses show that general strength training without supervision has no documented effect on running injuries. However, significant injury reduction is found when training is supervised and specifically designed for runners. Strong muscles, tendons, and joints can better handle the repeated impacts from running – but it requires the right approach.

Improved running economy: Stronger leg and core muscles mean you use less energy maintaining your running position. This translates directly to better times.

Increased power: Strength training develops explosive power, making you faster in the last critical kilometers of your 10km run.

At Nordic Performance Training, we recommend all our running clients supplement their running training with 1-2 weekly full-body strength training sessions.

For concrete strength training programs designed for everyone also runners, read our guide: [Full Body Program (1–3 Days/Week): Why Less Really Is More [2025 Guide]].

Frequently Asked Questions About 10km

How long does it take to run 10km for a beginner?

65-75 minutes is typical for beginners with a solid 5km base. If you can run 5km in 30-35 minutes, you can expect your first 10km around this time. The most important thing is to complete the distance – speed comes naturally with structured training over 8-12 weeks.

Can I jump directly from 5km to 10km without a program?

Yes, but it's not recommended. Although it's physically possible, it significantly increases injury risk and gives a worse experience. A structured 8-12 week progression program reduces injury risk by up to 50% and gives better long-term results through gradual adaptation.

Is 50 minutes on 10km a good time?

Yes, under 50 minutes (5:00/km pace) is a solid performance. It places you in the top 25-30% of Danish recreational runners and requires structured training with a good aerobic base. For context: beginners typically run 65-75 minutes, while elite runners break 40 minutes.

Should I take energy gel during a 10km run?

No, not necessary for most. For runs under 50-55 minutes, the body's glycogen stores are sufficient. For runs of 55-65 minutes, 1 gel at km 6-7 can help if energy drops. Important rule: Always test nutrition in training first – never experiment on race day.

What if I hit "the wall" at km 7?

"The wall" in a 10km run is typically mental, not physiological. Unlike marathon, the body has enough energy for 10km – the problem is often too fast starting pace that accumulates lactate. Solution: Practice negative splits in training (start slower, finish faster) and build mental discipline through interval training.

How many times per week should I run to improve my 10km time?

Minimum 3 times per week, optimally 4 running sessions. This provides sufficient training stimulus with enough recovery. Add 1-2 strength training sessions for best results. More than 5 running sessions weekly rarely gives better results for recreational runners and increases injury risk.

What's the difference between 5km and 10km training?

10km training requires four significant changes: (1) Longer easy runs of 10-16km to build aerobic capacity, (2) More threshold training in Z3-Z4 zones, (3) Longer intervals of 1200-2000m vs 400-800m for 5km, (4) Focus on pacing discipline and mental endurance through "the difficult middle" (km 4-7). Total weekly volume typically increases from 20-35km to 30-50km.

Conclusion

Running 10km isn't about talent or special physical abilities. It's about following a structured plan, building aerobic capacity, learning mental discipline, and maintaining patience through 12 weeks.

Regardless of which program you choose, remember:

- Progression happens gradually – be patient

- 80% of training should be easy (Z2) – it feels too slow, but it works

- Mental strength is trained like physical – "the difficult middle" becomes easier

- Recovery is training – don't underestimate it

- The most important run is the next run

After you've completed your first 10km or broken your goal, new opportunities open up. Maybe you'll want to improve your time further, try half marathon, or participate in one of Copenhagen's many running events like Royal Run, DHL Relay, or Copenhagen Half Marathon.

The most important thing is that you start. Choose the program that fits your level, put your first run in the calendar, and take the first step.

If you want professional guidance for your 10km training or want to combine running with structured strength training to maximize results and reduce injury risk, we offer a free start-up conversation where we can discuss how we best support your goals.

Referencer

Kakouris, N., Yener, N., & Fong, D.T.P. (2021). A systematic review of running-related musculoskeletal injuries in runners. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 10(5), 513–522. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33862272/

Oliveira, P.S., Boppre, G., & Fonseca, H. (2024). Comparison of polarized versus other types of endurance training intensity distribution on athletes' endurance performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 54(8), 2071–2095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02034-z

Wu, H., Brooke-Wavell, K., Fong, D.T.P., Paquette, M.R., & Blagrove, R.C. (2024). Do exercise-based prevention programs reduce injury in endurance runners? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 54(5), 1249–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-01993-7

Gabbett, T.J. (2016). The training-injury prevention paradox: Should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(5), 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788

Anderson, L.M., Martin, J.F., Barton, C.J., & Bonanno, D.R. (2022). What is the effect of changing running step rate on injury, performance and biomechanics? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine - Open, 8, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-022-00504-0

Casal-Hernandez, S., Martin-Miguel, I., Escriche-Escuder, A., Alonso-Calvete, A., & Abecia-Inchaurregui, L.C. (2024). Risk factors for running-related injuries: An umbrella systematic review. Journal of Sport and Health Science. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38697289/

Related Blog Posts

.svg)

.svg)

.svg.webp)